- Framing statement

“Live art can offer a place, a context and a process in which audiences can become involved or immersed in the creation of artworks” (Keidan, 2006, 14). Our performance Mapping the Lost City incorporated an exhibition of objects collected from around Lincoln. Stemming from an earlier idea of a smaller installation, we decided instead to create a whole gallery outside in the gallery gardens. It also included some audio of thought inspiring extracts, ones which would mean the audience could become immersed within the piece. With our use of performative elements in the space, our audience could also become involved with some small interaction. We aimed to make them feel welcomed into our gallery. A sense of life was important as it would prove a huge contrast to the discarded items we had collected. We had a curator who introduced the gallery and the experience. We made them available for questioning as this went against a typical gallery in which you never usually meet the curator. Our piece slowly became what we referred to as a type of anti-gallery. We displayed the pieces in small collective segments similar to that of a gallery but the piece as a whole did everything to contrast a galleries normal rules and atmosphere. Firstly it was outside and not confined between four walls, it was an exhibition of worthless objects, these objects were not protected or displayed behind glass or beautifully placed onto a plinth. We did not make any claims on the items or give the art any names. We just wanted to enhance the objects as what they were ‘broken’. We wanted to create an experience that would differ for each individual. An experience completely open to the interpretation of the user.

Change of Direction

In our original pitch we put forward an idea to incorporate homelessness. Our initial plan was to collect objects around the city which gestured toward homelessness and then we would aim to create an installation. We also wanted to include some sort of narrative that derived from these objects, incorporating a soundscape that made the public question what it is to be homeless? The gallery is a place of highly valued art and objects, placing this installation; we hoped would contradict to the space rather than conform. However, we realised that the homelessness aspect of the idea was unjustifiable in relating back to the gallery and so we had to re-evaluate back to the stemming point of the idea. We thought back to each idea separately. An installation. If the objects were not relating to homelessness, could they relate to something else? After some significant thinking we made a decision that will hopefully make a small yet effective change. We will now instead collect homeless objects, ones which are lost, abandoned or broken. Items of no value. Yet if placed in a museum, will the public’s perception of these items change? Would they be Art? Does a plinth, glass or a frame define whether an item is of value? We will become curators of an installation of Art that is essentially ‘rubbish’.

As a group we have also been highly interested in the idea of branching outside of the gallery and into a performance of the city “In contrast to the ‘White Cube’ gallery’s signification of emptiness, the urban landscape offers a profusion and complexity of signs and spaces” (Kaye, 2000, 33) we want to somehow take the signs of the city and create an experience that displays our objects in an imaginative process. Changing our museum from ‘Display to experience’ (Bennett, 2013, 8). The objects we will display will not be objects or the art that the public will be expecting. Therefore one of our focuses was to display these items so that they would appear visually stunning.

Inspiration and Transformation

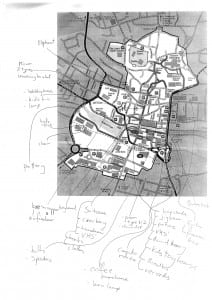

After thinking of ways to make our piece more of an experience, we decided to shift our work to the outside space surrounding the gallery. In doing this, we made the intertwining link of the gallery and the cities a lot less complicated and were able to expand on our ideas in more ways than one. We thought of ways in which we could use the outdoor landscape to our advantage and are hoping to display the objects creatively around the space. This enables the experience of a gallery to stay present even though the plinths and glass will no longer frame the ‘art’. We looked into the idea of psycho-geography and drew some inspiration from Carl Lavery’s 25 instructions for performance in cities. Lavery comments on performance as ‘learning to live creatively within your environment’ (Lavery, 2005, 231). How could we make our piece more engaging? We had to take a look back at some previous ideas and decided to follow through with an earlier suggestion to incorporate mapping. The initial plan was to represent, re-create and map Lincoln’s high street with the objects we had found. We wanted to create a sense of “Real space being written over by experience and imagination” (Performing the gallery). Due to various difficulties in the representation of the high street this idea had to change slightly. However, the objects being placed into the gardens potentially still wrote over the space themselves just by being there. When you exhibit objects, you automatically create an experience because you give the audience something to notice. As for mapping, we came to a decision to map solely through our own documentation. Marking off the objects we found onto a map of Lincoln. In doing this, we were able to notice various distinctions between different areas of the city. “City is a signifying system”(Performing the city). During the piece we also presented similar signals that were to be read but open to interpretation.

Audience participation

Audience swiftly became an important segment of our work. We had taken a look at the work ‘Nights in this city’ by Forced Entertainment. This particular performance consisted of a guided bus tour in Sheffield, where the ‘people on the streets became the unwitting material for the mythical representations’ (Tomlin, 1999, 41)Similarly to Forced Entertainment, we wanted our audience to use their own imagination to create some of the visual aspects of the space. Unlike forced Entertainment however, we would not be telling are audience what to picture. The audience were able to read the space in many different ways. We wanted our piece to be entirely interpretational. This links in closely to the idea of a visible and non-visible art. “The spatial juxtaposition of fragments can produce a representational understanding of the world”(Crimp, 1993, 60) Re-creating a display in the museums gardens is a juxtaposition of the picturesque greenery against the dissembled and deformed ‘junk’ we have collected from the high street. Making the high street the non-visible aspect of the performance we encouraged our audience to pay more attention to the display itself. During the process of this piece, Lincoln has ceased to look like nothing but a range of lost, broken and abandoned objects. When you stop to pay attention to these objects, the objects that would usually go unnoticed become the only things that you do. Another way we encouraged the audience to engage was by the use of performative elements. Just like any performance, our gallery needed an audience so that the creation of meaning did not get lost. The use of bodies amongst the objects meant our gallery gained a sense of life. “In order to fully grasp the intention of a space you have to take into consideration the people that inhabit it. Who are our target audience? Think about their reactions to the space, how they move within the space. Without them, the space would seize to fulfil its existence.”(Unkown) It was late in the process when we decided to include these elements. After testing out the piece beforehand, we came to the realisation that something more was needed in order for our piece to reach its full potential. Having them amongst the objects meant we were able to read the reactions of the audience and invite them in to the space. That sense of life created was aiming to gesture toward a narrative behind the objects, one which was untold.

Also as part of our documentation we want to incorporate how the audience map the space we create. We created an interactive task, so that the audience could involve themselves within the piece in more of a fun filled way. We created a key that consisted of four headings: – Cyborg Particles – Protectors – Familiar Findings – Adults Forbidden

They took round a map that represented the gallery space we were using for our piece. Then used the key to mark the objects with the colour coded stickers we provided. It was a task that enabled the audience to moderately trace our steps and grasp the overall experience of our personal process.

The process of Collecting

Collecting contributed as the principal focus of the process. From a very early point we had decided we would collect objects and create an installation. However, it was only after shifting to the outdoor space that we discovered exactly how many objects we would need to collect to ensure the public would have enough to engage with within the space. As a group and individually we would go out into Lincoln a few times a week to collect objects which were lost, abandoned and broken, we wanted to ensure that our findings were of an outstanding standard. At first we were not too sure on what it was we were aiming toward, therefore we were slightly confused on what objects would be best to collect. What size? Would they need to all relate to each other? “Objects play a crucial role as material evidence supporting a particular version of the world”(Stead, 2007, 38) The world we were supporting was one in which was discarded, we wanted to create a ‘storehouse of shattered things’ (Auster, 1999, 78). We picked up everything we could and gradually we were making small relations between objects and constructing smaller collections from the larger collection. We kept collecting right up until the day of the performance. It was a “Continuous process during the piece and a residue of the process of the entire piece”. The map also creates itself another map, one in which we coordinate and navigate the space around the objects. We carefully documented every item we collected by marking it off onto a map and annotating the findings. Now, although the site performance has finished, we are able to keep the documentation as a reminder of the whole performance.

The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster helped us to define our intentions and aims within the piece. The novel involves the collecting of discarded items. There is a specific focus on the objects losing their original function. “Because it can no longer perform it’s function, the umbrella has ceased to become an umbrella”(Auster, 1999, 76.) If something is broken, does it then become something else? Does it obtain a new function? This is the direction we were aspiring toward in the piece. All the items we placed in the gallery were broken; therefore they could no longer perform their original function. By placing them in the gallery we automatically gave the worthless worthiness. The point of our piece was that no one exactly knew quite what it was, yet they still felt intrigued enough to take a look or ask questions. “The brokenness is everywhere, the disarray is universal. You only have to open your eyes to see it. (Auster, 1999, 78.) Brokenness is pushed aside to invisibility, therefore the audiences engagement proved the performance success. An underlying theme also touched upon “The broken people, the broken things, the broken thoughts” (Auster, 1999, 78.) It was left completely to the interpretation of the audience, but the idea that these objects referred to a broken society was also something we aimed to signify very briefly. We took extracts from the text that we could use in an audio piece that accompanied the audience as they navigated themselves around the space. We used extracts that did not make our intention obvious. We wanted them to be thought inspiring, extracts that enabled the audience to make their own decisions and own narratives. It was important for us not to block any narrative ideas. Unlike a gallery, we did not what to claim a truth over any of the objects or give any of the artefacts names. “Museums are among the ‘documents’ of this historical era concerned with the problem of naming”(Lord,2006,7). As stated in the framing statement, our idea slowly became an anti gallery. We resisted conforming to the rules of a typical gallery and instead did everything we could opposite.

We were inspired by Blast Theory’s use of sound and although our idea was very different to their pieces. We did incorporate the use of headphones. This encouraged our piece and made our performance personal to each individual. Along with the extracts from New York trilogy. We also had a soundscape of the city. “Modern Art needs the sound of traffic outside to authenticate it” (Doherty, 1999, 44)

Performance Evaluation

On performance day, we were faced with various challenges. Most of these were because our piece took place outside. We had prepared for rain, having umbrellas provided for the audience members. However we were not entirely prepared for the wind. Once we had got ourselves together as a group. We allowed the weather to work to our advantage. Broken tapes we had wrapped around a stairs barrier blew out creating beautiful shapes. We also had young audience members playing with this particular piece. The wind also blew some of our records off that went on to roll down a hill. All this brought a new sense of life to the performance because unlike a gallery we were not protective over the work; we had to let whatever happened happen. For instance, one man moved the wedding dress slightly and seated himself beside it. This created a lovely image, as the wedding dress was stuffed to look as though someone was sat inside it but no one was there. Therefore new narratives formed in my own head and I knew that this would effect the audience perception too.

The inclusion of the mapping task allowed us to cater to all different types of audience members. It proved an enjoyable participatory activity for families. We had public members who preferred not to listen to the audio and then those who only wanted the audio. Being able to provide one or the other or both meant that our audience satisfaction was attended to.

Works Cited

Auster, P. (1999) The New York Trilogy. London:Faber and Faber

Bennett, S. (2013) Theatre and Museums. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Crimp, D. (1993) On the Museums Ruins. MIT Press.

Jowitt, D. (1997) Meredith Monk. Art + Performance 1-49.

Kaye, N. (2000) Site Specific Art. [online] London. Available from http://lib.myilibrary.com/Open.aspx?id=32715 [Accessed 29th March 2014].

Keidan, L. (2006) This Must Be The Place. In: Leslie Hill and Helen Paris (eds.) Performance and Place. London:Palgrave Macmillan, 8-17.

Lavery, C. (2005) Teaching Performance Studies: 25

instructions for performance in cities.Studies in Theatre and Performance, 25 (3) 229-238.

Lord, B. (2006) Foucault’s museum: difference, representation, and genealogy. Museum & Society, 4(1) 1-14

O’Doherty. (1999) Inside The White Cube: The Ideology Of The Gallery Space.

Stead, N. (2007) Performing Objecthood. Performance Research, 12(4) 37-46.

Tomlin, L. (1999) Transgressing Boundaries: Postmodern Performance and the Tourist Trap. Arts & Sciences III, 2, 136-149.