Framing Statement.

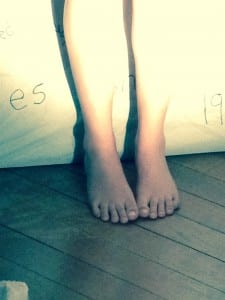

Exposing the Silent is my feminist site specific performance that took place in the Usher and Collection in Lincoln on 10th May 2014. The performance was two hours long, split between the morning and afternoon and consisted of myself lit with minimal lighting, taking a male shirt off to reveal feminist quotations from literature on my back and, after a timer bid me to after a minute, I replaced my shirt and sat back on the plinth. My key influences during this process were Marina Abramović, Janet Cardiff and Claire Blundell Jones who are all females producing artistic performances in non-stereotypical sites, exploring the ideas of physical labour; restricted spaces with civil codes created by society; touch; and the body. The role for the audience during my performance was to simply act as voyeurs because it was about the ignorance upon women that society had in James Usher’s lifetime and it portrayed minimalism in order to reflect the lack of influence women had and still have today in some cases.

Week 1.

My initial class on Site Specific revealed that it is a risky, challenging style of performance that opposes the typical canonical drama that resides within theatre space. In my performance I wanted to integrate this through asking what art is, and questioning the significance of the canon and its representation within a patriarchal state.

The class also discussed the importance of temporality within a space and the idea that ‘museums are also heterotopian for Foucault: they are those sites in a culture designated as spaces of difference, spaces in which ordinary relations within the culture are made and allowed to be other.’ (Beth Lord, 2006, p.1).This states that a museum is categorised as heterotopian in Foucault’s language because the space itself is within our present culture but the interior reflects that of various histories and geographies – it is several cultures within one. Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks reiterate this point in Theatre/Archaeology when they write, ‘So too we emphasise that site is as much a temporal as spatial concept – landscapes are enfolded; scenography works with the multidimensional temporality of memory, event and narrative.’ (2001, p.55).

Lastly, we considered aspects of collections due to the museum and gallery being a collection of artifacts. We asked ourselves subcategories came within the overarching idea of collection: the domestic, belonging, national, conceptual, and feelings of ownership. Three of these (domestic, belonging and ownership) influenced my performance in terms of the ideas these themes encouraged. There are many similarities between a collection and the idea of marriage within the Victorian and Edwardian eras in which James Usher lived. Furthermore, domesticity is recapped through the knowledge that the Usher gallery was once the residence of James Usher himself.

What is a ‘site’?

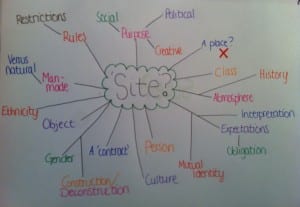

What is a ‘site’? This was one of the questions dealt with in our first class to which, admittedly, I immediately thought ‘a place’ in reply. However, reflecting on this answer afterwards I realise that a site involves many variables and therefore defining it as ‘a place’ simply isn’t sufficient.

Firstly, the place is occupied by something that defines the space itself; this could be anything from an object, to a person, to the light that creates a specific atmosphere. The next aspect of a place that makes it a site is its purpose. As well as this the people within it either fulfil a purpose, or are obligated to act accordingly to the restrictions that the space requires. This is particularly interesting because, whilst a purpose defines the site itself, it indirectly creates a common or mutual identity that all occupants of the space must obey – like signing a societal contract only relevant within that specific space. The space creates similarities between separate people and crosses boundaries implicated by society (for example, race, class and gender), therefore creates an opportunity for encounter between those unlikely to meet in a different site.

This provoked me to ask these questions when considering a site:

1 What is its purpose?

2 How is the space constructed according to its purpose?

3 What is my place within the site?

4 How are my rights as a person considered within the space as opposed to other sites?

In Mike Pearson’s book Site Specific Performance he suggests that this performative style questions not only the meaning of the place by being situated within it, but also the meaning of the art and performance itself. He goes on to question why this art must be placed within the confines of a theatre in order to be taken seriously throughout the rest of the book. (Pearson, 2010).

Pearson goes on to quote Tim Ingold’s statement that, ‘places do not have locations but histories’ (2000, p.219) so suggesting that a site is also defined by the history of that place. Therefore a performance within that space ‘engages intensively with the history and politics of that place, and with the resonance of these in the present’ (McAuley, 2007, p.9) which means that the performance is responding to the history, culture and politics that inhabit the space, or previously inhabited the space. Pearson is implying that Site Specific performance is a reinterpretation of the space and its meaning – it is defamiliarising what the audience may already know which makes this style of theatre self-conscious. By doing this the performance raises questions concerning spatiality and the meanings constructed by it.

Week 2.

This is the week that I first visited the site in which I would be performing by the end of the process – the Usher and Collection. I chose to perform in the Usher due to my stimulus being situated there, however the museum was a significant space in terms of research and the ideas I gained from it that influenced the questions I wanted to raise within my performance. Abigail Levine correctly states that, ‘the museum is a space that grants social and historical significance to an artist’ (2013, p.295) as you cannot think of one without the other within these spaces, and it was crucial for me to comment upon this from the very beginning. I also portrayed the idea that Pearson and Shanks acknowledge about museums when they say, ‘the material and ineffable immediacy of the past has given it a special place in constructions of personal and cultural identity.’ (2001, p.53) This states that past is used as a means of identifying the nation, and oneself within the social confines of any given space. It shows the power that history has in shaping the identities of the descendants of those creating it. I demonstrated this through my use of literary quotations that connects to ideas about society and women at the time through artistic means, and I deliberately used quotations from James Usher’s lifetime to set it in a history that affects us very much today and is in a time that isn’t inconceivable.

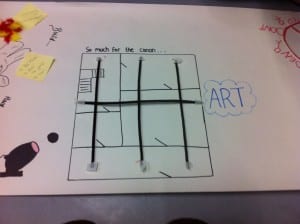

On arriving at the gallery we completed various tasks in which I had to imagine what the walls within the space would say. I created a diagram in order to represent this:

This shows a floor-plan of the gallery which is covered by prison bars with the word art on the exterior of this space. The canon in the bottom left corner just shows the idea that the gallery only exhibits artistic creations that are stereotypical within our culture. Lord writes that, ‘museums are monuments of the eighteenth-century drive to categorize, classify, and order the world into a totality universal in scope and universally intelligible.’ (2006, p.2) I remember laughing at the irony that we were supposed to perform non-stereotypical live art in a site that didn’t seem like it would appreciate it. This is an argument that was evident in my final performance because I was criticising the use of female nudity within the gallery and the idea that it was considered art. Also, I noticed the reactions of an audience of the nude drawings, paintings and photographs as opposed to the reactions to a very limited view of nudity that was live. I had my back to the audience but many of them still reacted in a way that I expected occasionally, which was to escape the room as soon as I removed my shirt. Again, I thought it ironic that they would welcome images of nudity but not the reality of it, and it supported my opinion that society gives us certain codes that people secretly, and often without knowing it themselves, abide by.

Throughout my experience of visiting the Usher and Collection I realised that it was an extremely restricted area which became very frustrating as I was attempting to think of ideas of performance, and each idea arose various problems due to the rules that the space ensured. I devised a list of rules, examples of which were: do not run, do not shout, do not take any liquids into the gallery, do not use pens, do not touch anything. I also noticed there were a lack of places to sit so I added ‘do not sit’ to the list in a way of protesting. My performance contained a lack of movement and speech due to the first two rules aforementioned, and to represent the stillness as opposed to ephemerality. I also sat on a plinth for the majority of my performance and, although I did not allow the audience to touch me, nor I touch them, I did use the element of touch towards the end of my performance in order to feel my clothing and to eventually replace the shirt with the underwear and dress that lay about me on the floor. The idea of opposing rules within my performance came to me from seeing Claire Blundell Jones’ Spooning (2010) which was a very simple performance that invited audience members to ‘spoon’ the performer in order to touch people in a site where touch is forbidden.

I gradually progressed my performance from routine to rebelling because I wanted to show the progression that women have made up until the present with their rights and treatment. Although there is obvious room for independence and control in my characterisation, she finds the courage to ignore the temporal rules forced on her by a patriarchal space and she finds the strength to speak ‘voice. I deserve a voice’ (Demi Mayne, 2014) before she makes the decision to exit the space in which she felt she was trapped earlier on.

Finally, the idea of giving an invitation to the audience was revealed to us, which is very often done in Site Specific performance in order to gain audience members. This made me think of the idea of interpretation and the fact that each audience member would perceive something different of my performance, which interested me greatly. Therefore, this further encouraged me not to speak during my performance so the audience could interpret the visual aspects as they preferred, and also started me thinking about putting myself in another person’s shoes (as the saying goes) in order to empathise and portray this concept of individuality. This was my first thought to the end product of my performance.

Week 4.

In week 4 we had to write a response to one of the pieces of art in the gallery and I chose The Woman in a Kimono by Austin Garland. Ideas of entrapment and imprisonment resonated within the work for me, and it highlighted the significance of appearance for women today, but especially in historical context. When performing this to the class and onlookers several problems arose which enlightened me to the complexities and difficulties I had to consider for my final performance. These were:

1. People lost interest – to solve this I made my piece a short 1-2 minute performance that progressed over the entirety of the performance time. Therefore some members of the audience saw the repetitive beginning and others saw the breaking of these routines, or both.

2. Spatial awareness – many people became engrossed in the performances but after a period of time became aware that they could be in somebody’s way and left. I avoided this problem through placing myself in the corner of an empty room so that the audience could fill the remainder of the room without worrying.

3. Language – I noticed that some language used in some of the performances were inappropriate for young audiences and therefore made the conscious decision to be careful about the language I used. By week 6 I had decided to not use any language at all as this created a societal boundary and lack of room for interpretation.

4. Noise/projection – performer’s voices were often lost over the noise of the space. This was yet another reason for me not to use audial but instead focus on the visual aspects.

5. Dominating a space – the need to show that you are there and performing for a reason. I decided that if I didn’t prove my purpose quickly enough the audience would lose interest and I would lack voyeurs, especially without the use of my voice and extensive movement. This, again, supports my idea for a snappy performance that people could leave quickly and have gained an understanding.

Week 4 also revealed Marina Abramović to me through the documentary on The Artist is Present (2010). Her work includes nudity, and through this challenges the audience and becomes a feature of the space of the museum. She also created her own space in the video and performed within this space to minimise intervention. This creation of space erases the idea of time and gives value to stillness and silence. As you can probably tell, this all influenced me massively in terms of stillness, silence and the creation of my own space that held its own sense of time. The element of time was incredibly important because it controlled everything within the space, including myself until my character decided to rebel against it and find her freedom and voice.

Just as Janet Cardiff’s Her Long Black Hair (2005) uses repetition for effect, so does my own performance. ‘The repetitive utterance performs the ubiquitous historical loop of bodily constraint that resonates in so many of these vanished sites…’ (Carmen Derkson, 2012, p.9). My performance, however, represents the historical loop of mental constraint that resonates in the site of the female mind, and still represses women in the patriarchal society that continues today.

Week 6-8.

Within these three classes I pitched my performance concept and refined it due to problems within the space. Firstly, due to everything previously mentioned, I wanted to be nude in my performance because I could not comment on the nude art if I wasn’t in the same position as the victimised. Originally, I wanted people to write their thoughts and feelings in response to nudity on my skin and I would become an installation in the second hour for a separate audience to reflect upon. However, I came to the conclusion that this was trusting the audience to write sensible comments too much, and also broke the gallery rule of not using a pen or liquids. My way around this was to write on myself (with help from an artist) but without the audience’s responses I didn’t know what the content was going to be. I began to research feminists and quotations on the internet but kept coming back to the idea that it did not link to the space enough. It occurred to me, then, that literature is a type of art, and that it often reflects societal views in the context the novel was written but within a fictional world. So by week 10 I had decided upon quotes from North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell; Women in Love by D.H. Lawrence; The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne; The Moon and Sixpence by W. Somerset Maugham; and the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw.

Rehearsal week – performance day.

During rehearsals I decided upon minimal lighting that was a neutral colour to allow the audience their own interpretation upon the subject of feminism, nudity and body art. I also decided to have an element of timer which is when I thought of the idea to use an egg timer to reflect domesticity and patriarchal control (as mentioned in the rest of the blog above) but the egg timer broke on the second usage in rehearsal! So I used my phone, which fitted in the neutral, white colour theme and was more reliable and reflected a modern society within a performance reflecting the past (1845-1921) so was used as an anachronism. As Lord writes, ‘the museum is ‘progressive’ – progressing out of Enlightenment values of universal truth and reason – because it can critique those values, and yet it cannot perform this progressive critique without relying on the Enlightenment values at the basis of that notion.’ (2006, p.3).

My performance ‘is by nature synecdochic. A limited repertoire of sign-vehicles generates a potentially unlimited range of cultural units.’ (Pearson and Shanks, 2001, p.55) I aimed to represent every woman through the lack of speech, movement, facial expression and neutral lighting in order to make it an accessible performance, and I believe I achieved this. In the afternoon I had a large audience that seemed to watch intently, whereas the morning performance and in rehearsal I had not received this good a reception. The majority of the end of my performance was improvisation, although I had been thinking ideas such as speaking the final words before leaving the room, and ideas of dressing in the last 30 minutes of my performance in rehearsal. I decided to act upon these ideas because it reflected modern day society more clearly and I wanted to show that society had progressed, as I wasn’t aiming to criticise, only to draw awareness.

If I were to perform this piece again, I would write over the majority of my body so the feminist quotations were more of a spectacle and piece of artwork. I would also invite the audience somehow, whilst keeping with the idea that the audience had the power of choice; whether to watch me or not. Whenever an audience member walked out of the room it proved my point that we are still living in a patriarchal state, and that people are very accepting of nudity in unrealistic doses, but once it becomes realistic it makes society uncomfortable. But why? I noticed that children, with their innocent minds and lack of shaping from societal pressures, were more accepting of nudity than their parents and the elderly.

Overall, I was extremely happy with my performance, the audience and the reactions I got. I believe I conveyed my purpose successfully and even though the improvisation at the end was nerve-racking, it was also exciting for both the audience and myself.

Works Cited:

Derkson, Carmen. (2012) Walking the Edge of the Stage in Theory; or, Janet Cardiff’s Sensorium for Intermedial Bodies. Theatre Research in Canada, 33(1) 1-23.

Ingold, T. (2000) The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London, Routledge.

Levine, A. (2013) Being a Thing: the Work of Performing in the Museum. Women and Performance, 23(2) 291-303.

Lord, B. (2006) Foucault’s Museum: Difference, Representation, and Genealogy. Museum and Society, 4(1) 1-11.

Mayne, D. (2014) Exposing the Silent. [performance art] Lincoln: Usher Gallery, 10th May.

Mayne, D. (2014) Fig.1. Advertisement photo [Taken] 23rd March.

Mayne, D. (2014) Fig.2. What is ‘site’? [Taken] 11th February.

Mayne, D. (2014) Fig.3. Canon Gallery [Taken] 20th February.

McAuley, G. (2007) Local Acts: Site-Specific Performance Practice, Introduction. About Performance, 7, 7-11.

Pearson, M. (2010) Site Specific Performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pearson, M. and Shanks, M. (2001) Theatre/Archaeology. London: Routledge.

Walsh, A. (2014) Fig.4. Performance torso [Taken] 10th May.

Walsh, A. (2014) Fig.5. Performance feet [Taken] 10th May.