Framing Statement:

Mapping the Lost City encompasses an exhibition of which we have curated through lost, broken and abandoned objects left in the streets of Lincoln. Accompanied by the use of audio, the audience themselves attempt to document the city by mapping the gallery space in the Usher Gardens. The soundscapes that aid the performance consists of snippets of Paul Auster’s text, The New York Trilogy, and the sounds of Lincoln’s streets which were recorded in the route of which we found a majority of our objects.

Our exhibition is not an extension of the gallery space; it is a response to the site and reacts against the norms of housing art. Essentially we have created an anti-gallery space in which audience are not restricted in taking photographs of the art, but invited to do so. Furthermore, by holding an exchange we are providing visitors the chance to take our pieces of art as long as they replace it with something of their own possession. We are also curating our work in front of audience members in the morning which never occurs in a regular gallery setting, thus further breaking the boundaries of gallery-worthy art. Ultimately, we question and challenge the realms of artistic expression by displaying discarded objects as highly valuable collectables.

Our performance aims to unlock the space that we are in, thus allowing participants to navigate around the Usher Gardens. It is a durational performance from 11:00-15:00 and consists of an installation, soundscape and various sit-ins with performers amongst the artwork itself. The audience are as much a part of the performance as we are. Their response to the art displayed is pivotal to our concept of portraying junk as appreciated objects worthy of value.

Process:

What makes art?

Art -noun:

‘The expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power’ (Oxford Dictionary, 2014).

Art is perceived to possess creativity, ambiguity and prestige within our society. Having visited the Usher Gallery, I looked around at an array of different pieces of art, each with different hidden stories, interpretations and inspirations. No one piece was the same, yet all were applied with the same creative skill. What they did share in common was a general sense of appreciation for the artist’s work. There are clear instructions which tell you to not touch the pieces, you must behave in a respectful manner whilst visiting the gallery and even, in some cases, there were barriers protecting the art. This interested me, the insistence of protection of art within the Usher Gallery. If, like the Oxford Dictionary suggests, art is ‘to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power’ (Oxford Dictionary, 2014), then why are all pieces of art not appreciated with such prestige?

In many ways, this video showcases a cultural experiment taken out by Banksy leading me to the question: how do we constitute what is art? As Dissanayake suggests the status of art can, in some cases, be wrongly attributed as ‘art may be a value laden term that we use carelessly and misleadingly’ (Dissanayake, 1988, 59).

Banksy’s experiment fundamentally exploits and confronts the values of commodification of the arts by eliminating the conventional role of the ‘artist’ as producer when exchanging pieces of his work as he remains anonymous. Not only does he challenge what art is, but he also foments the discussion of cultural hegemony as the idea of social class within his art is eradicated and questioned. The destruction of the role as producer of the art allows a political statement of art culture to be formed. This idea of the exchange and housing of art is something that is evidently explored within most art galleries, including the Usher, and is something that we first considered whilst creating our own performance.

Having first explored the Usher Gallery, we were particularly engaged to certain pieces of art which channel the realms of what is accepted into the industry as artistic greatness. One common theme that seemed to recur amongst the pieces of work is the idea of rubbish and how it can be presented as art. For example, the grand chandelier, Tide, made of broken pieces of glass juxtaposes grand beauty with something which is deemed as broken and useless. The notion of what society deems as rubbish is something that we first began exploring in our investigation.

The Value in Collections:

Both the Usher Gallery and Collection Museum possess highly valued collectables as they house various items from historical artefacts, grand cutlery sets and an array of oil paintings. All of the above collections are treated with such respect whilst guarded behind the confinements of glass cabinets and signs informing that you must not touch the artist’s work. This therefore led myself to the question: are all collections valued collectables? Paul Auster’s novel City of Glass, follows Stillman, a person who wonders the streets of New York collecting a vast amount of abandoned items. Stillman claims that every object has a similarity, that similarity being that every item has to perform a function. Stillman uses an umbrella to explain himself: ‘an umbrella is an umbrella because of its function to protect us from the rain, if it is stripped of its material is it still an umbrella?’ (Auster, 77, 2011) Stillman’s quest to acquire broken objects and give them new definitions inspired us for our performance as we decided to obtain lost, broken and abandoned objects and give them a new meaning within a gallery setting. Some may ask: does putting these items in a museum or gallery make them art or something to be respected? In placing these everyday objects in a site such as the Usher and Collection it automatically changes the object’s function as it becomes something to be appreciated, not used.

John Dahlsen’s ‘Multi Coloured Plastic Installation’ piece is valued at $14,000, a small amount of money in comparison to other artists such as Damien Hirst who sold his piece ‘Lullaby Spring’ for $17.2 million in 2007, but a lot of money nonetheless. Essentially Dahlsen has curated a valuable piece which was created through unvalued objects. To the naked eye, these objects would not be deemed as art, but by carefully curating them as part of an installation in a gallery the objects take on a new function. Ultimately, ‘there is no way to establish the quality of a certain picture or oeuvre. One cannot even judge objectively whether a given work constitutes art or not. No technical or logical standards exist by which to proceed. The quality of art cannot be proven or disproven by scientific method’ (Bonus and Ronte, 1997, 104). Rather, value in the arts is often attributed through social contexts such as the site of which it is displayed and the status of the artist themselves. This provided our group with an interesting line of investigation as we continued to question the conventions of gallery spaces and how artists can present discarded items in artistic ways.

Psychogeography–An Exploration of the City:

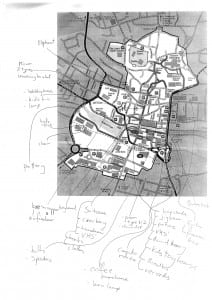

Guy Debord became an influence whilst collecting broken objects, as we focused our walks on ‘one of the basic situationist practices…the dérive, a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiences. Dérives involve playful-constructive behaviour and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll’ (Knabb, 2006). Having started to explore the city as an urban space, we began collecting our findings as we searched for discarded treasures. Certain traits started to exist amongst the city as we collected items from the city and documented our encounters on maps. Interestingly, certain items are only found in differing parts of Lincoln. For instance, parts of the city remain untouched by what the public would see as ‘litter’ whereas other areas saw such high volumes of cheap cigarette packets, broken bottles and other abandoned domestic items. ‘For contemporary psychogeographers, the drift is purposeful; it can reveal the city’s underlying structure’ (O’Rourke, 2013, 13). We created geological maps that do not necessarily document place names; rather they document the city through an exploration of discarded items.

Ultimately, our performance aimed to make people pause, look and contemplate these unwanted objects that we encounter on a daily basis within the city. In placing these objects, of which we encounter on a regular basis, in the Usher Gallery, they are transformed from the discarded to the aesthetically pleasing. Talking of performance artists Townley and Bradby, Simone Hancox states that their walking-based practices aimed ‘to challenge the hegemonic uses of urban space and diminish the hierarchy that is associated with the artist as producer and the audience as consumer’ (Hancox, 2012, 4). In many ways our performance, which was heavily reliant on audience participation to walk around our gallery space, allows the spectator to take on the role of performer as they navigate their way through our exhibition. Therefore, we challenge the norms that define artistic practice by placing the spectator at the heart of our work.

Furthermore, as we furthered our ideas we met many obstacles when clarifying our concept. Essentially we aimed to create a gallery space outside of the Usher Gallery in the gardens – in many ways we have created an ‘anti-gallery’. Mapping the Lost City creates an inversion of the gallery space as we do not present the perfect – instead we present imperfections through an array of lost, broken and abandoned objects. In doing so, we discussed that we should totally reverse the ‘laws’ of the gallery by allowing the audience to speak with the curators during the performance, by allowing people to take photographs of the art and by giving the audience the chance to take certain pieces of our art as long as they replace it with something that they possess.

Psychogeography–The Art of the Process:

Whilst on the quest to find lost, broken and abandoned objects we encountered various obstacles within the process – many of which have benefited the process towards creating our performance. Navigating the city searching for objects allowed us to freely explore different areas of Lincoln until we noticed and documented certain traits in different areas of Lincoln.

Whilst collecting our pieces of art from the streets of the city, several members of the public speculated on what we were doing. People were shocked and appalled as we rummaged through used belonging on the streets – even a member of the city council approached us questioning our reasoning and motives. In explaining to these spectators that we were creating an art installation of these broken objects that we were collecting we were often met with a surprised expression from the member of public. They may not have been aware at the time, but essentially through that conversation we are questioning what exactly art is as they were forced to think how, what they may deem to be rubbish, is now going to be presented in a gallery setting. In many ways, these members of the public are turned into our audience members as the process of collecting becomes part of our performance to some extent. Much like Luke Jerram’s Sky Orchestra, part of our audience may never have been aware that they were in fact part of a performance.

The Rubbish Collection:

Whilst researching various artworks created from junk, I came across Joshua Sofaer’s latest project, The Rubbish Collection. This installation piece was curated from one month’s worth of rubbish from the Science Museum’s waste. The rubbish is no longer seen as waste once placed as part of an installation piece in a gallery space, thus highlighting to the audience that ‘the things we throw away do not disappear but are transformed’ (Sofaer, 2014). Sofaer clarifies, ‘museums generally display items that have some special status, that are rare, or valuable. But in this project, I want to give the ‘museum treatment’ to the stuff it would normally throw away’ (Sofaer, 2014). In placing items of which appear to have no intrinsic value in a gallery, a spectator is forced to see how the objects are transformed into a piece of art. Therefore, the site of which an item is placed evidently manipulates the audience’s reactions to the artwork.

Sound Ecology:

Once we found the majority of our objects I started to explore how the use of a soundscape can enhance our performance. Talking of soundscape ecology, an article in the journal BioScience explores the ‘assignment of a soundscape to a geographic context…and spectral and temporal patterns in the soundscape, how disturbance alters patterns’ (Dumyahn et al, 2011, 204). He also highlights ‘the emphasis on interactions between biological and anthropogenic factors’ (Dumyahn et al, 2011, 204), something that we definitely explored when recording the audio of the streets of Lincoln. Once editing the audio, I noticed such distinct differences in sound. Usually, navigating a space in which you are accustomed to, a sense of sound can often get lost in the quest to get somewhere. However, I found the process of recording these sounds an enlightening one as I was suddenly made aware of such distinct differences of sound in varying areas of Lincoln. Furthermore, we have hoped to emulate this sense of truly listening to the sounds of which you are presented with by fragmenting the audio with silence and loud soundscapes of busy streets. In many ways, through the use of audio, we are rewriting over the space of which we inhabit in the Usher Gardens by temporarily transporting the audience through the medium of audio. Blast Theory summarises the benefits of soundscapes in performance as they remain fascinated with how ‘technology creates new cultural spaces in which the work is customised and personalised for each participant and what the implications of this shift might be for artistic practice’ (Blast Theory, 2014). Please find below the audio that accompanied our audience members in our performance:

Social Objects:

Essentially, museums and galleries house objects to instil thoughts, emotions and ignite debates amongst their viewers. Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum asks for people to ‘imagine looking at an object not for its artistic or historical significance but for its ability to spark conversation’ (Simon, 2010). As we reached closer to our performance, my group and I carefully thought about ways to make these broken items something more than just junk. When trialling our piece we realised that the audience do not have to care about what they are looking at if they are simply placed on the ground in the hope that they investigate them. Taking into consideration the ephemerality of some artworks, in the sense that a lot of visitors only gaze at pieces for a short amount of time, we had to figure out a way of creatively ensuring that the participants engage with our items for a longer period of time. As a result, we decided to incorporate maps of which the audience can participate, if they choose, to map out what objects fall under different keys which we provide. The keys are: Cyborg Particles, Adults Forbidden, Familiar Findings and Protectors.

Now, with the aid of mapping and audio, the audience will navigate the space paying attention to the items of which are displayed in front of them. Therefore, the objects have the potential to become an ignition for social debate as they all suggest different things to different audience members. The interesting part for us as the curators of this performance arrives when we document our audience’s responses as they categorise the objects with the keys. Discussing art in gallery spaces, Morris denotes that ‘our encounter with objects in space forces us to reflect on ourselves, which can never become ‘other,’ which can never become objects for our external examination’ (Morris, 1993, 165). Hence, our curated objects are not only something for aesthetic inspection; but they also ignite a reflection on what these pieces mean to oneself. This was also aided by the decision to have sit-ins of which performers are amongst the art themselves, thus colliding the world of object and performance based art practices.

Furthermore ‘walking blurs the borders between representing the world and designating oneself as a piece of it, between live art and object-based art. Artists moved from depicting places to pointing them out or demonstrating them’ (O’Rourke, 2013, 13). In curating these objects as a part of a walking-based performance practice, the audience members explored the thresholds of the space, paying close attention to each piece of art, both object and performance art.

Evaluation:

Overall, I believe the performance was very successful as we engaged with varying members of the public through their navigation of the Usher Gardens. The responses to our objects were very positive and people took their time whilst exploring each collection, mostly treating these pieces as valued artworks.

One area of improvement that we could have worked on and changed was the amount of audience participation that we had allowed the audience to engage with. In many ways, the installation, audio, performer sit-ins and maps was too much to participate with. In hindsight, our expectations were highly ambitious and perhaps did not give each audience member the time to fully engage with each element of our performance. However, I noticed that different performative elements engaged certain members of the public, more than others. For example, families who visited our exhibition revelled in the idea of searching through our art pieces to find which objects matched the keys on their maps and documenting the process. This led to various debates between the audience members as they discussed what they personally thought each object fell under which key. Conversely, other members of the audience were far more engaged by the installation itself, accompanied with audio and the sit-ins. Whilst incorporating all of these elements in our piece allowed us to engage with a wider demographic of people, we could have perhaps refined our ideas to sustain the spectator’s focus.

We had hoped for the audience to exchange a possession of their own for one of the art pieces, yet the rain meant that we had to pack up early. However, what was interesting throughout the day was the assumed allowed physical interaction between the art and the spectator. There were no instructions for the participants to physically interact with the objects. Interestingly, many individuals moved parts of our installations, played with the objects and, in one case, stole a part of the record collection. One man even sat himself down on the bench where the wedding dress was displayed; thus creating a perfect juxtaposition for our piece, whilst not being intended. The contrast between this beautiful gown and the casually dressed man who sat next to the empty garment furthered our intention; as we presented conflicting images throughout our installation of broken objects within the prestigious gallery space. Interestingly, this interaction with the installation would not occur within the confinements of the gallery building, thus highlighting that art is affected by the site of which it is presented. If these pieces were displayed inside the building, I believe it would not have been met with the same assumption that the audience were allowed to move the installation pieces.

Another successful element to our performance was the audio which interacted well with technology as we made the soundscapes accessible via MP3 players, YouTube and, for ease of access, QR codes. Essentially, our performance now exists within the realm of the internet as people can still listen to the soundscapes that we created to accompany our performance.

Ultimately, we explored and challenged the thresholds of the space that we were in by allowing the public to engage in a geographical exploration of our site, whilst responding to the gallery itself through curating broken items. Fundamentally, our performance successfully questioned the art industry as we reacted to Edelsztein’s belief that ‘art is garbage…garbage could be art – if the artists wants so’ (Eldelsztein, 2007).

Mapping the Lost City transformed ‘junk’ into pieces of artwork which were appreciated for their aesthetic qualities, and their ability to infuse thoughts into the audience. It is through the placing of these broken objects into a gallery setting that transforms them from pieces of rubbish to valued collectables. Jeff Ferrell perfectly summarises that, ‘as we dug in Dumpsters and accumulated scrap and reinvented what we found, we watched the status of everyday objects drift between wished-for possession and forgotten waste, useless castoff and usefully reconstructed tool, trash pile discard and outsider art’ (Ferrell, 2006, 161). Ultimately, I believe that we pushed the limits of what could be considered artistic and exploited the space of the Usher Gardens; thus making connections between discarded items and valued treasured pieces of art within a gallery space.

Works Cited:

Auster, P. (2011) The New York Trilogy. London: Faber and Faber.

Blast Theory (2014) Blast Theory. [online] Available from: http://www.blasttheory.co.uk/our-history-approach/[Accessed 26 March 2014].

Bonus, H. and Ronte, D. (1997) Credibility and Economic Value in the Visual Arts. Journal of Cultural Economics, 21 (2) 103-118.

Cahill, M. (2014) Mapping The Lost City. [online video] Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JbV-YXa6pQY[Accessed 9 May 2014].

Dahlsen, J. (2013) Multi Coloured Plastic Installation. [online] Available from: http://www.johndahlsen.com/detail_installation_art/multi_colour_install.html [Accessed 15 February 2014].

Dissanayake, E. (1988) What Is Art For? Washington: University of Washington Press.

Dumyahn, S., Farina, S., Gage, S., Krause, B., Napoletano, B., Pieretti, N., Pijanowski, B. and Villanueva-Rivera, L. (2011) Soundscape Ecology: The Science of Sound in the Landscape. Bioscience. 61 (3) 203-216.

Eldelsztein, S. (2007) About Action Art, the Museum and the Object Between. [blog entry] 01 October. Available from: http://performancelogia.blogspot.co.uk/2007/10/about-action-art-museum-and-object.html?m=1 [Accessed 11 May 2014].

Ferrel, J. (2006) The Empire of Scrounge: Inside the Urban Underground of Dumpster Diving, Trash Picking, and Street Scavenging. New York: New York University Press.

Hancox, S. (2012) Contemporary Walking Practices and the Situationist International: The Politics of Perambulating the Boundaries Between Art and Life. Contemporary Theatre Review. 22 (2) 1-27.

Haygarth, S. (2004) Tide. [installation] Lincoln: Usher Gallery.

Knabb, K. (2006) Theory of the Dérive. [Online] Available from: http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/2.derive.htm[Accessed 12 March 2014].

Lawrence, C. (2014) Mapping The Lost City. [Taken] 10th May.

Morris, R. (1994) Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris. London: MIT Press.

O’Rourke, K. (2013) Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers. Cambridge and Massachusetts: The MIT press.

Oxford Dictionary (2014) Art. [online] Available from: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/art[Accessed 12 February 2014].

Simon, N. (2010) The Participatory Museum. [online] Available from: http://www.participatorymuseum.org/chapter4/[Accessed 9 March 2014].

Sofaer, J. (2014) The Rubbish Collection. [online] Available from: http://www.joshuasofaer.com/2014/04/rubbish-collection/[Accessed 17 March 2014].